1 Scalar Transport in the Atmosphere

1.1 Basic Principles

Consider an element of air containing a concentration  of a passive

pollutant (passive means that it doesn't react and is neutrally buoyant, i.e.

it doesn't settle).

of a passive

pollutant (passive means that it doesn't react and is neutrally buoyant, i.e.

it doesn't settle).

Fig 1. As an element of air is carried along by

the flow it always contains the same air and therefore contains the same

mass of pollutant.

If the flow is also incompressible, then the volume of the fluid element

remains constant and so the concentration  remains constant. In mathematical

terms

remains constant. In mathematical

terms

It will be sufficient for our purposes to take the air to be incompressible

so that

Hence an alternative form of Eq. (1) is

Suppose now that there is a source or sink of the pollutant within the

element of air. This could be because the pollutant is created or destroyed

by chemical reactions or because there is an outflow from, say, a chimney.

The equation for  would then become

would then become

where  represents the source term (in kgm

represents the source term (in kgm s

s ). Examples could

be:

). Examples could

be:

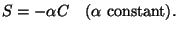

(i)

(5)

(5)

This represents decay of  by, for example, chemical decomposition or

radioactive decay.

by, for example, chemical decomposition or

radioactive decay.

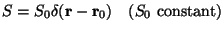

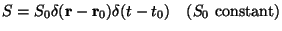

(ii)

, (6)

, (6)

where

is a delta function at

is a delta function at

.

This represents a continuous point source (e.g. emission from a chimney).

.

This represents a continuous point source (e.g. emission from a chimney).

(iii)

. (7)

. (7)

This represents an instantaneous point source occurring at time  at

at

(e.g. accidental release of a radioactive substance).

(e.g. accidental release of a radioactive substance).

Another type of source/sink term is caused by diffusion. The pollutant

may diffuse in or out of our element. The equation for  is then

is then

is the molecular diffusivity.

is the molecular diffusivity.  has dimensions

has dimensions

.

Typical values for pollutants in the atmosphere are 5-50

.

Typical values for pollutants in the atmosphere are 5-50

m

m s

s . We are usually concerned with dispersion on the scale of

hundreds of metres to hundreds of kilometres. Consider

. We are usually concerned with dispersion on the scale of

hundreds of metres to hundreds of kilometres. Consider  m. Then

the time-scale is

m. Then

the time-scale is

which is infinite for all practical purposes. Hence molecular diffusion

is never directly relevant to atmospheric dispersion.

1.2 Turbulence

Atmospheric flows are almost always turbulent. Turbulence occurs when

the Reynolds number is high. It is characterised by eddy motions on a wide

range of scales. When describing the dispersion of pollutants, we are usually

interested in dispersion on scales much larger than many, if not all, of the

eddies. In other words, we are interested in averages over length or time

scales large compared to the turbulence.

In order to analyse dispersion in this way, we assume that it is possible to

divide the flow into a ``mean'' flow which is slowly varying in time and a

rapidly fluctuating, or ``turbulent'' part. We could perform this separation

by defining an average as follows:

The average period  should be chosen to be long compared to the turbulence

time-scales. Then we put

should be chosen to be long compared to the turbulence

time-scales. Then we put

represents the turbulent part of

represents the turbulent part of  . It follows (to a

reasonable approximation at least) that

. It follows (to a

reasonable approximation at least) that

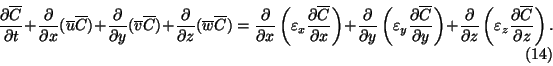

Let us perform this separation for all the variables in the concentration

equation, Eq. (3).

Therefore

We now average this equation. Consider, for example

since

. Similar results hold for

. Similar results hold for  and

and  , giving

, giving

The right-hand side represents the average effect of turbulent eddies on the

concentration. Molecular diffusion is caused by the random motion of

molecules, whereas the effect here is caused by the random eddy motions. By

analogy with the molecular scale, we assume that

,

,

and

and

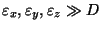

are analogous to the molecular diffusivity

are analogous to the molecular diffusivity

. They must be measured experimentally. They differ from

. They must be measured experimentally. They differ from  in that

(i)

in that

(i)

,

,

and

and

need not be equal,

(ii) In general,

need not be equal,

(ii) In general,

,

,

and

and

are not constant,

(iii)

are not constant,

(iii)

.

.

Using Eq. (13),

This equation is the basis of much of the modelling of atmospheric dispersion.

back to syllabus

![]() of a passive

pollutant (passive means that it doesn't react and is neutrally buoyant, i.e.

it doesn't settle).

of a passive

pollutant (passive means that it doesn't react and is neutrally buoyant, i.e.

it doesn't settle).

![]() remains constant. In mathematical

terms

remains constant. In mathematical

terms

![]() would then become

would then become

![]() is then

is then